This is another piece in the prism that the Motivation Series turns out to be ... Not what I intended to write, but what came to me basically by accident: there seems to be a core divide between games that either make rpg challenges mundane by having powerful characters OR making everything challenging by having mundane characters in dangerous situations. Why is that? How does it work? And why aren't others talking about it? Let's see (and yes, this will eventually be about gaming, of course).

You want to start reading at the beginning? Here's Part 1

There's also an Intermission about how computer games shaped our expectations, and you can read that here.

What makes us laugh, divides us ...

So here is what happened: Pratchett died (bear with me), and no one writes as funny as he did. At least no author I could get my hands on. Sir Peter Ustinov was just as funny, but didn't write as much and died even earlier (which doesn't help).

Now, people will tell you that humor is a matter of taste, and I will tell those people that taste is a matter of specific biological and psychological conditions which need to be understood to make any meaningful contribution to any art we attempt. Doesn't matter how abstract the grip is we get on the topic, we need to have SOME UNDERSTANDING about taste to interact with it. It's disingenious and lazy to try and stop a discussion with "that's just a matter of taste".

Another perspective on humor is that laughing is the spontanious (and possibly shocking) realization of a connection we haven't seen before. Why is it funny when somebody stumbles? Possibly because we didn't realize what movements a body is capable of to desperately keep balance? There is no such thing as "stumbling with grace", which leads to "people take themselves too serious to allow for stumbling". So you could say it's the spontanious insight that we are taking ourselves too serious that makes us laugh when we see others stumble.

|

| ... [source] |

Oh, and there's always the aspect that we laugh when nothing is really hurt but another person's dignity. If an old lady falls and is at risk to break a bone, you get there and help her and ask her if she's alright. That's not what I'm talking about.

There's also Jackass, so there is a spectrum on how much pain can still be funny ... But that's neither here nor there. What I wanted to show was that humor has reason and has a function in a culture. Or even in general among humans ... and we do know that animals can laugh, which is also very interesting. We instinctively know it is important. It is an easy connector in any conversation. If you can make people laugh earnestly, you know you will get along with them. Just like that.

However, to go full circle: while taste should never be the end of a discussion when talking about creating a specific kind of experience (as that's what we do: design talk), it's very much a marker of preferences that should be taken seriously in order to find out why they exist and how they are, lets say, activated. And Pratchett was a huge and popular marker in that regard. He was the GOAT, without a doubt. And no one seems to be able to crack his formula. His writing doesn't even translate well to other media (other than rpg, maybe, but definitely not for tv).

|

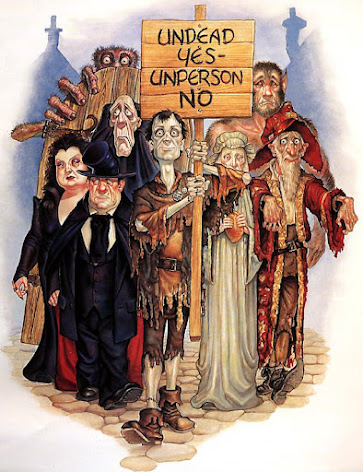

| Always had great artwork, though ... [source] |

I'd argue that ONE aspect of it is that he described very real people in very bizzare circumstances. Imagine being a photographer for a newspaper, but you are a vampire and using the flash will actually turn you to dust, so you have to take precautions ... Pratchett is full of ideas like that. Undead fighting for their rights in society, politicians dealing with trolls and dwarves and dragons, but those all behave like people you might encounter in daily life, too.

Fantasy and the (British?) 20th Century mindset juxtaposed like that is a huge part of where Pratchett's books draw humor from, often to slyly tell us something about the human condition we hadn't realized yet.

|

| Some good reading [source] |

Still, didn't click for me right there. Made me think about the issue again, though.

What did the trick was reading another author after that who also was celebrated as very funny, although more in the manner of Monty Python. I dig me some Monty Python, the story sounded rad, so I took a chance (and probably made the mistake to read it directly after the Times). That book was Rober Rankin's Retromancer.

In all honesty, I didn't enjoy it as much as The Stranger Times, and I couldn't put my finger on why exactly that was. The premise is great. Guy wakes up in the Sixties, but it isn't the Sixties he knew. No. Here, it seems, the Nazis had won WW2 by bombing the US into nuclear winter. So that guy gets to rejoin his Master, a great wizard and guru, to set the timeline straight again. A bit of Monty Python, a bit of a Peter Sellers routine, full of great ideas and great little story vignettes.

Great writing, too. I'd have loved to see it as a movie. But as a book, it just didn't work for me. It was in direct comparison to that other book that it dawned on me: the characters in Retromancer are anything but mundane. They are, in many ways, larger than life. Not only "the guru's guru", but his sidekick, the narrator, as well. Not someone you relate to, but a character you know from movies. Superficial, in a sense, and with a "funny" perspective on things that colors the whole story.

A character like that (as in: extraordinary) going for breakfast (as in: doing something ordinary) will have the most extraordinary adventure doing so (goes for a good old english, gets a Bratwurst, or as his aunt puts it "the Führer of all sausages", which I actually found immensely funny). This character will buy some cigarettes, and you'll have the most beautiful little stories about smoking throughout the book. Ordinary things made extraordinary by the extraordinary character ... you get my drift.

There's a theme, even!

You could make the same distinction between the horror Stephen King is summoning versus the horror a Clive Barker will summon. King's characters are real or "mundane" in that we can empathize with them. Barker's are bizzare minds putting a bizzare lens on reality. Two very different qualities, but qualities with the same differentiating element: they either use the ordinary to explore the extraordinary or they use the extraordinary to explore the ordinary.

Same goes for computer games, I'm pretty sure. On the one side you have some open world games where characters start from zero and carve themselves a niche into the sandbox as they see fit and on the other side you have those ultra complex quick time event driven games that hold your hand for the story and most of the progression, but pushing the right buttons at the right time will have a character make some really crazy moves (Arkham Asylum, Metal Gear Rising).

|

| Me, everytime ... damn qte! [source] |

Either way, it's a thing for sure, and once you are aware of it, you'll find it is a very strong theme in tabletop role-playing games as well. As a matter of fact, I'd go as far as saying that it is one of the distinguishing factors in role-playing games right now. And it is definitely leading to different design choices along the way. Not BETTER or MORE FUN, but DIFFERENT. As in: so different, people will most likely be into one OR the other (or at least more into one than the other).

And that's what this post is about: showing that there is a DISTINCT difference between those two modes of play and that they not necessarily (or easily) mix. It is not an evolution of gaming, it is manifesting a divide that always has been there.

Different styles altogether?

So far we have the outline of the distinguishing factors. On the one side you have rpgs that start with a couple of in some sense ordinary characters (usually a beginners of sorts) who face an extraordinary situation (classically, exploring some dangerous ruins with magic and monster abound). That's your basic early D&D, but most ttrpgs up until the nineties would follow that recipe more or less.

Prince Valiant: The Story-Telling Game was in 1989 an early precurser of that shift we are talking about here, but the big success in that regard was Vampire: The Masquerade. The tag line back then had been very apt, it was a game about playing THE MONSTER. All of a sudden you'd be way above humans in the foodchain, and in a contemporary setting, no less. Still small fries, all things considered, but powerful small fries.

|

| Classic rpg fork [source] |

Still, it turned out to be the starting point for a clear trajectory, with the PbtA games as one high watermark and the Black Hack games as another.

Interestingly enough, there seems to be a trend to glorify the original beginner characters from early D&D towards the extraordinary. My guess would be that it has something to do with loading the characters with some meaning they didn't have before, like PUNK, for instance. It's pretty much the Robert Rankin approach described above, where the lense through which the player/character see the world colors everything mundane in some special light.

There's also a massive manga and anime trend to have ordinary people become extraordinary because they end up in extraordinary circumstances (like a fantasy setting, but are actually very capable in that setting compared to the real world (where they might be nothing!). In other words, ordinary characters turned extraordinary because their extraordinary surroundings are just ordinary for them is a classical trope by now, which might explain the appeal in role-playing (which follows the same meta-knowledge metric: players knowing the rules fare better).

Blades in the Dark is a more recent powerful contender for the "extraordinary characters" category as well and The Spire RPG seems to be the newnew hot in that regard (giving players lots of narrative power, for instance).

D&D 5e tries very hard to be that kind of game but obviously brings a lot of baggage to the table, which will make it a great example for how different those games actually are and how it's more like a spectrum on the user end of things. Because D&D was the original blueprint of all things rpg, it will have always had room for the story-telling gamers.

You can't, on the other hand, play ordinary characters in games that are designed for extraordinary characters only (unless you go for the comedic break of the ordinary character doing ordinary things among extraordinary characters). We tried, actually, in one of our groups once. Was a new group, didn't last, btw. I had offered to DM the WitchCraft rpg and I told the players that it is about powerful characters in an urban horror/fantasy setting.

All agreed and knew what was what, but as soon as character creation started, half the group wanted to play ordinary characters in a horror setting. WitchCraft doesn't work that way and that led to many discussions why there is no tension for the ordinary characters. They just didn't get that they were talking a different kind of game. As I said, didn't work out in the end, and it was more symptomatic that the game played out as it did. But it illustrates my point: original D&D could have been played that way (and there actually are urban fantasy b/x variants out there), WitchCraft was designed to NOT do that.

There's also the little fact that playing the first editions of D&D will grow a character from wimp to god and one could always just start with a more powerful character along that trajectory (Goblin Slayer would make for a D&D campaign like that).**

But who likes to play what and why?

Different players altogether?

I might have to start with a disclaimer here. First of all, people will change between the "roles" in their life. A loving mother can be a bloodthirsty barbarian on her weekly gaming night. People play to relax. To be someone else or to be among friends or because the gaming immerses them. This is, in a sense, where we connect a bit with Part 1 of the Motivation Series, but only to (maybe) add another facet to it.

Here's the part I'm talking about (5 positive motivations for players to join your game):

- DOING

something meaningful (mainly socialicing with others for a collective

experience ... leveling up & campaign play as milestones, those things)

- LEARNING something meaningful (collecting experiences & testing approaches to reality)

- COMPETING meaningfully (negotiation, tactics & strategy)

- BEING someone meaningful (exploring who you are or aren't & why)

- CREATING something meaningful (a game, an experience, a story)

I'd say that players going for "extraordinary characters" would, going by the 5 types of motivation proposed in Part 1, be mostly among the people motivated by BEING someone special and those aiming to CREATE an experience. COMPETING and LEARNING motivations would gravitate more towards that are challenging and offer some more skill oriented growth (instead of, say, personal growth). Those in it for DOING it as a social activity could go either way, so we'll have an even split among motivation types. Nice!

The new aspect here would be, then, that finding out what actually motivates people in joining your game is actually quite easy. You just ask them if they'd rather play (A) an extraordinary character doing ordinary things or (B) the other way around. There are three possible answers: A, B or "I could go either way, I'm in it to socialize with friends" (or something along those lines ...).

An "I don't know" shouldn't cut it, to be honest. Sure, talk it out, but if one of the three possible answers doesn't appear naturally relatively fast, it would hint (imo) towards a motivation that hasn't anything to do with gaming. Just something to be aware of, I guess.

|

| Just saying ... [source] |

Still not where I wanted to be with this, BUT another important piece, imo, as we will need to talk about what different kinds of role-playing games are out there and why that matters immensely in terms of player motivation. What we got to explore in this post helps shining a light on some of the distinctions.

That said, being aware of the axis described above should be useful in itself as it should help you in finding an understanding about why we play the games we play and why some will work for you and some won't just because of some design choices that aim to please a ecrtain type of player.

By accident or consciously doesn't matter, if you think about it. Sometimes it's just a designer's raw preference that resonates with likeminded people. What does matter, however, is that is not "all the same".

I hope I was able to make my case here and that you guys enjoyed reading this. What do you think the implications are? Did it change your perception about your preferences? Thoughts and opinions are, as always, very welcome.

------------------------

If you enjoyed the above, you might like the blog anthology series I started publishing on drivethru. You can get it here and it definitely supports the blog to drop by for the pdf here.

AND I'm still hustling this one: You can check out a free preview of Ø2\\'3||, that rpg I wrote, right here (or go and check out the first reviews here). I'm (still, but only until end of June) doing a sale on the game proper ...

If you already checked it out, please know that I

appreciate you :) It'll certainly help to keep the lights on here! I'd love to hear about that, too.

|

| Just look at that beauty ... |

* I have to figure out how tactic, card and puzzle games figure into that, but I think they might just be something else entirely, leaning towards boardgames and such.

** Okay, here is yet another dimension to this: it is known that many D&D campaign fail when the characters becoem to powerful. Mostly that'd be because the DM didn't shift gears along the power curve and challenged the more powerful characters with something adequate. But in a sense it shows how players who like to play ordinary characters in extraordinary circumstances, actually don't like it when the game turns that around after a couple of levels. Anecdotal evidence, for sure, but nonetheless. It fits the pattern, doesn't it?